You can't change history—but you can interpret it.

In many education systems, history is the study of linear, cause-and-effect events that culminate in our present. This understanding of history prepares students for standardized tests but fails to capture the messy, complicated, and ambiguous nature of the study; History is fickle, contorting to fit the ethics, culture, and beliefs of the person recording or relating it. It, therefore, requires peer review, ideally by those with deep knowledge or direct experience of the historical events in question. In Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca (Voyages of the Great White Fleet) 1899-, Enrique Figueredo acts as an artist and a historical peer reviewer of Imperial Spain's history.

What's in a name: The Historical Roots of Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca

In 1907 President Theodore Roosevelt sent 16 state-of-the-art US battleships on a world tour to demonstrate America's naval superiority. The ships took on the name "The Great White Fleet" for their conspicuous white paint. The ethos of the expedition followed President Roosevelt's uncompromising foreign policy position best surmised by the phrase, "speak softly and carry a big stick," but Roosevelt's display of military might also bore an uncanny resemblance to the colonial exploration, expansion, and conflict affiliated with Imperial Spain's transatlantic military expeditions.

Roosevelt's Great White Fleet bearing an uncanny resemblance to Imperial Spain's flotillas.

THE ZOETROPE's form As A TANGIBLE LINK TO THE COLONIAL PAST

In 1834, in the epicenter of the world's largest colonial empire, a British mathematician named William George Horner published a paper on his new invention, the Dædaleum, better known today as the zoetrope.

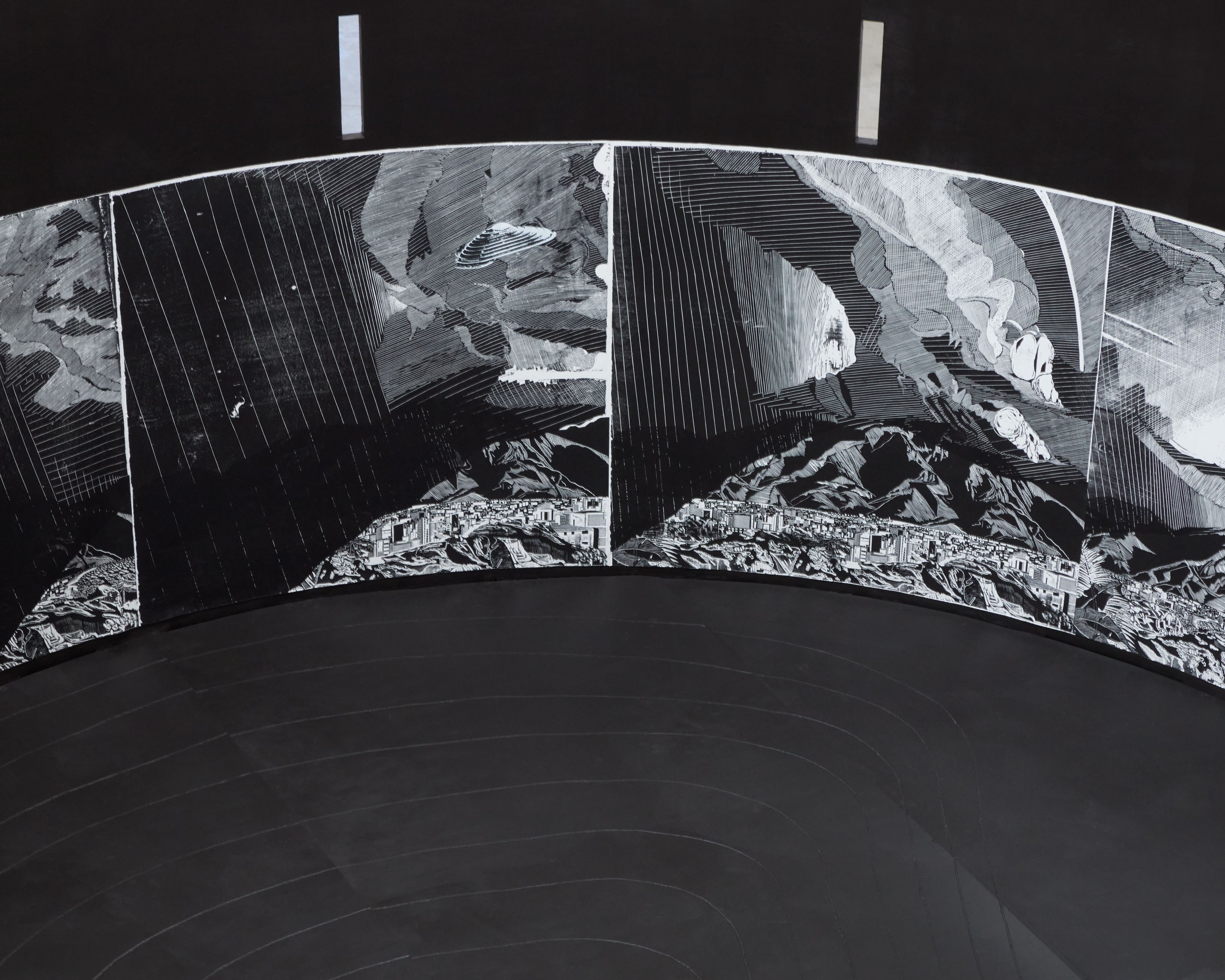

A precursor to film animation, the zoetrope consists of a hollowed-out cylinder with a sequence of images adhered to the interior. Vertical slits cut into the sides of the cylinder provide a window through which users can view the image sequence. When spun, the images flicker past the zoetrope's vertical slits, creating the illusion of movement.

What it looks like to view the animation of Figueredo's Zoetrope.

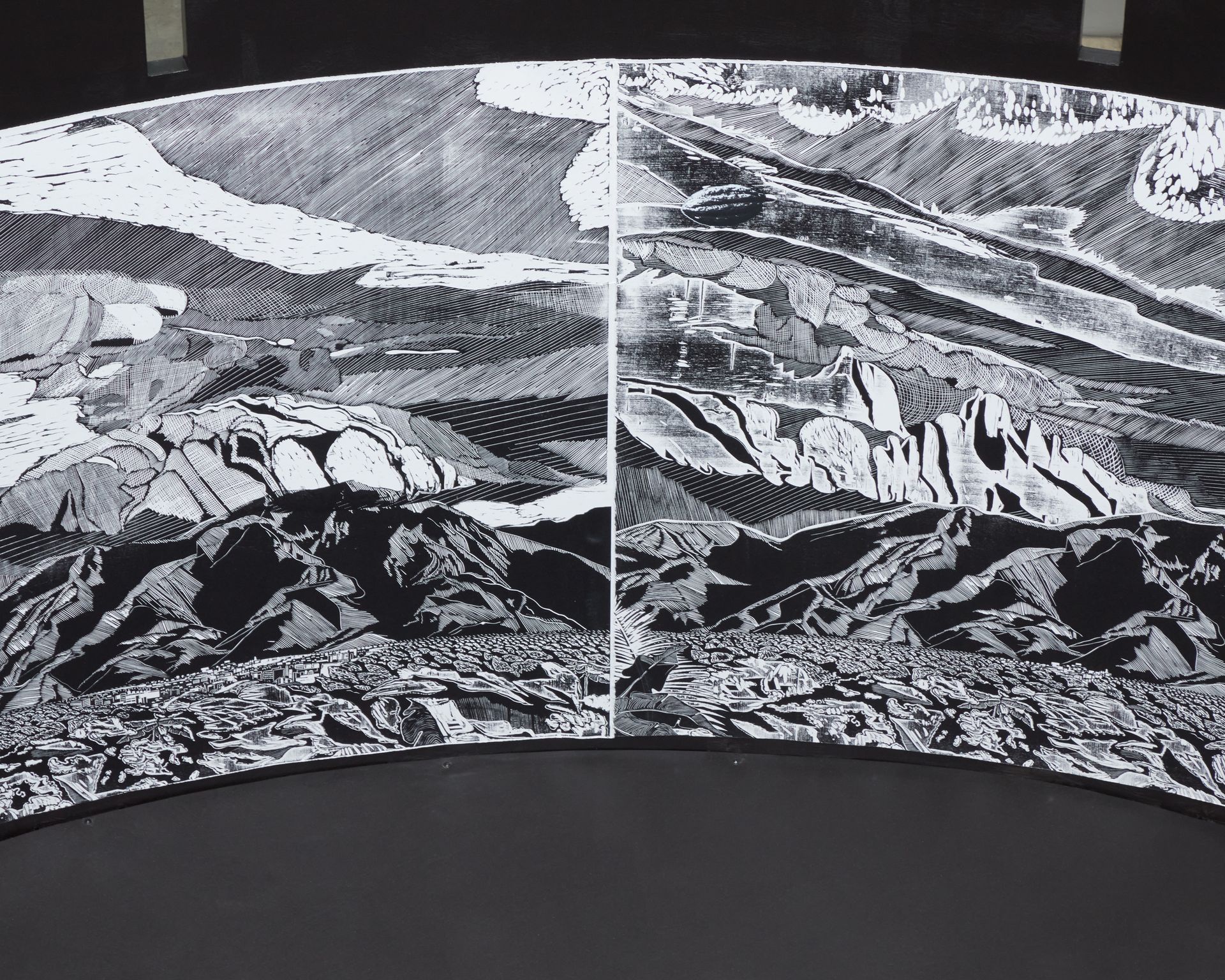

Two of the prints from Enrique Figueredo's massive zoetrope. Each panel is printed from a hand-carved woodblock.

Today, the zoetrope is a footnote in motion picture history. But in the 19th century, the zoetrope was a tool, a scientific discovery that demonstrated how we interpret the natural world. The culmination of efforts by opticians, philosophers, mathematicians, physicists, and artists, the zoetrope sits at the intersection of many of the pursuits that constitute civilization, making it a tangible link to the historical period whose residues Figueredo continually encounters.

Measuring 6 feet tall and 15 feet across, Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca figuratively scales the impact of Spanish colonialism on Figueredo's hometown of Caracas, Venezuela.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

With the conceptual impetus for the zoetrope taking shape, Figueredo's next step was fabricating the work.

It took over a week of 12-hour days to fabricate Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca. The final sculpture stands just over 6 feet tall and measures 15 feet in diameter. The print series inside the zoetrope depicts a storm rolling over the city of Caracas. A singular UFO (echoing the pyramidal architecture of a prison in Caracas) rides in on the storm clouds, implying the arrival of visitors from another place, an event not unlike the arrival of the Spanish in Venezuela in 1499. Informed by centuries of European ethics, culture, religion, and a staunch nationalistic attitude, Spanish conquistadors arrived in Venezuela with an agenda: to glorify Spain and increase the country’s global political and economic power, whatever the cost.

A lone UFO careens over the iconic mountains of Caracas; What could it want?

By 1577, Spain had entrenched itself in South America, particularly in Caracas, which yielded a boon of textile products, livestock, and gold for the Spanish empire. The gold of Caracas, and many other South American colonies, became the primary channels of wealth that funded Spain’s colonial expansion in the Americas.

Uninhibited by financial limitations, Spain enjoyed military supremacy in the region, creating the perfect socio-political climate to exercise soft coercion and allowing Spain’s presence and influence to spread, much like the dark clouds that consume Caracas in the animation of Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca. Each revolution of the zoetrope reminds viewers of the induction and visualization of circular time, the cyclical nature of globalization, and the repetitions of history.

SPECTACLE OR INTERACTIVE PERFORMANCE?

The zoetropes of the late 19th century depicted simple sequential action, making it easy for viewers to understand the intended animation. For example, a zoetrope depicting a running horse only makes logical sense when read in a single direction. But Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca is different. It portrays a storm, a natural event that reads equally well regardless of the zoetrope's rotational direction. The storm might be rolling in, but it could also be dissipating.

Because Viajes de la Gran Flota Blanca is hand-powered, people ultimately control the animation the object creates. In a sense, the functionality of Figueredo's zoetrope mimics the nature of history: What we see depends on our engagement; What we learn from history depends firstly on us, our capacity to appreciate multiple interpretations, our ability to acknowledge suppressed narratives, and perhaps most importantly, our decision to participate in history or watch it unfold from afar.