Katrina Bello, portrait by Molly Wagoner

Spencer Linford: Most of us are familiar with the personification of nature as “Mother Earth” or “Terra Madre,” but could you explain your interpretation of this concept as it relates to the work you create, both thematically, and literally? With this question, I’m thinking specifically of the role your daughters played in the exhibition, from appearing in your Lupain video series to crafting the ceramic trays of Color (7,400 miles), Line (RA: 2h 31m 48.7s, Dec: +89° 15' 51"), and Air (Storytellers).

Katrina Bello: Terra Madre or Mother Earth was such an apt title for the show because it tied together the “mother” theme that is common to all the works in the show. As an artist who makes work about our complex relationship with the natural world that we live in, I’m interested in the Gaia hypothesis—and it’s not only a concept that I think of when I’m making the works in the studio; it’s also the idea that pervades my interaction and research into the natural surroundings that are the references for my works. Whether my research process involves hiking, exploring, observing, photographing, taking videos, or collecting grasses, soil, rocks, tree bark from deserts, mountains, coastal areas, or prairies (and in any weather condition too, with a preference for windy or even stormy days), I tend to have a very physical and tactile involvement with my surroundings. And when one is touching and feeling soil, rocks—running one’s hand through water and sand; listening to the sound of the wind; hiking and scrambling to collect videos and photos while it’s raining—one can really feel the land, water, rocks and soils as fellow living and speaking entities, with the Earth as our mother. There’s also the reference to my mother and my own experience of motherhood. Not long ago, I came upon this short poem by Nayyirah Waheed:

my

mother

was

my first country

the first place i ever lived

To me, the poem provided the connection that I was looking for to unite and articulate what I wanted to express but couldn’t fully verbalize when it comes to making artwork about motherhood, nature, the environment, and the very physically involved process that I employ when I do research and observation outdoors.

Finally, my daughters have been regular participants, as well as subjects, in my works, but it wasn’t always clear to me why I was drawn to having them involved. But just recently, I may have found that connection through the repeated travels (2023 to the present) that I’ve been doing to visit my daughter, Kamilla, and my mother. One of the most memorable moments during those visits to my daughter is brushing her long hair. In doing so, I was finding analogies between her hair and the patterns in the landscapes I viewed from the airplane that I take when I travel to visit her.

Top: Kamilla Bello's hair, photo courtesy of the artist

Bottom: Ulmus Pumila bark, photo courtesy of the artist

Above: Aerial landscapes from Katrina Bello's travels, photos courtesy of the artist

This led me to find more analogies between her hair, tree bark, rocks, and also my mother’s skin. Working on the Air, Line, Color objects with Kamilla was the first time that I put these ideas beyond two dimensions and into a more sensuous tactile form.

Color (7,400 miles), 2025. Ink drawing on clay, yellow ochre, and black sand; ceramic tray by Kamilla Bello, 7 3/4 x 7 1/4 x 1 3/4 in (19.7 x 18.4 x 4.4 cm)

SL: Three works, Lupain (Ulmus Pumila), Lupain (Posoge 1), and Lupain (Posoge), comprise the centerpiece of Terra Madre. Could you explain how you chose the subjects in these marquee drawings; how they relate to one another; and perhaps how these drawings can, through their regional context, help us better understand cultural ecology on a broader scale?

KB: The main point of departure for these three drawings was being awarded the artist residency at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation of New Mexico, and having the time, studio space, and lodging located in surroundings that resonate with my ongoing works about land, bodies of water, the environment, and human relationships with the non-human world. Siberian Elm trees (Ulmus Pumila) surrounded my casita at the foundation (pictured below).

A snapshot of the Siberian Elms outside Bello's casita at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, NM, photo courtesy of the artist

And Posoge (the name that the Pueblo people gave the Rio Grande) and Rio Grande Rift were a short driving distance from the foundation. In addition to their being ideal subjects since I was already working on the topics relating to tree bark and bodies of water, the Siberian Elm tree and the Rio Grande also provided analogies to another theme that my work touches on: immigration. It’s only recently that I’ve been comfortable mentioning my experience of immigration as an influence in my work. Instead of discussing openly about my personal experience, I found instances and narratives in nature that allude or find parallels to my experience and the experience of other immigrants.

With Lupain (Ulmus Pumila), the Siberian Elm tree provides an analogy as the non-native species that eventually thrives and becomes a contributing member to its surroundings, especially in the high desert in northern New Mexico.

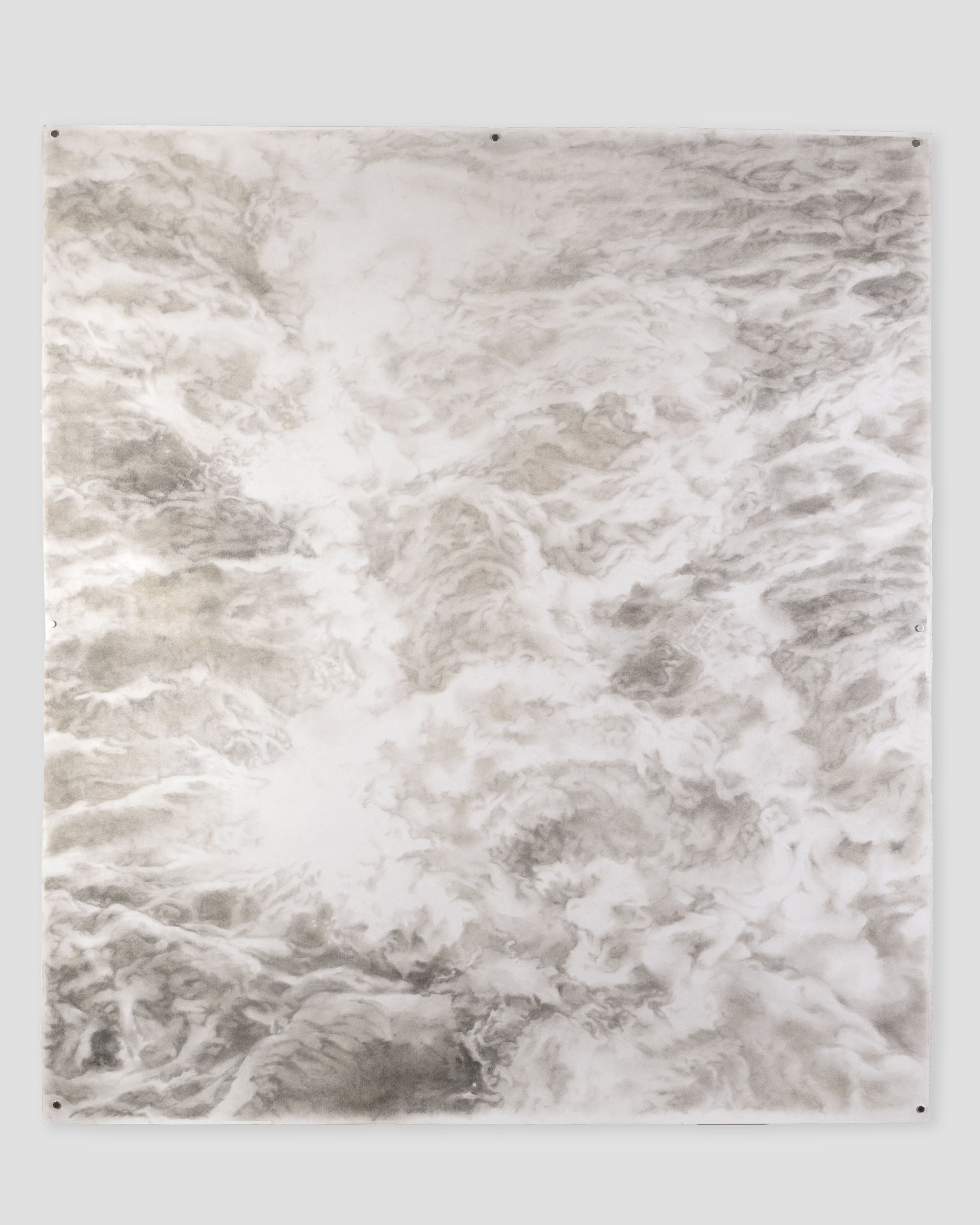

Lupain (Posoge), 2023. Charcoal and pastel on paper, 53 1/2 x 48 in (135.9 x 121.9 cm)

And as for Lupain (Posoge 1 and Posoge), they’re an allusion to the many cases of bodies of water that are sites of actual migration, including the Rio Grande.

Lupain (Posoge 1), 2023. Charcoal and pastel on paper, 53 1/2 x 48 in (135.9 x 121.9 cm)

SL: Metaphorically, it could be said that you see the world through your preferred drawing mediums: charcoal and pastel. You crush these organic substances into powder and then turn them into lens filters to use on your camera in your Lupain (Haplos) Series. How does introducing a digital tool like a camera into your creation process change or not change the work you ultimately produce?

KB: A friend, colleague, and curator just recently told me that I am really a photographer, but I’m just not aware that I am. I’m still pondering this. I’ve never taken a photography class, but photography and video are necessary components of my studio practice. Because the drawings are strictly made indoors in my studio, the only way I can refer to the places that I use for the drawings are the videos and photographs that I take. But recently, especially during artist residencies, I’ve been spending more time working on photography and video because of their portability in remote places and my constant traveling. Where I feel it has changed the drawings is how such documentation helps me create a form of storytelling through photos, videos, and writing that provide the viewer with context.

Installation, Lupain Series 1-8, 2023-2025. Metal print, 7 x 5 in (17.8 x 12.7 cm) each

SL: Yakap (Embrace) is a deeply personal piece. Could you, if you are comfortable, bring us back to what it felt like for your family to move from Davao? What was the experience of relocation like, and how has it informed your work?

KB: It’s indeed the most personal piece I have ever made because my family’s move from Davao to Manila was a change that I was not prepared for, and thus traumatic. I didn’t really feel homesick for Davao until I immigrated to the United States not long after moving to Manila. I believe that my being drawn to landscapes and bodies of water in my work and making large drawings of them is a form of remaking and reconnecting to the sense of the landscapes and seascapes of Davao that I can no longer go home to, to reverse the feeling of being truncated from the place. I mention truncated because of the scar on my left arm that spells “putol”—it is the Filipino word for “cut,” “separated” or “truncation.”

Yakap (Embrace), 2025. Bronze and black sand on a ceramic tray by Kamilla Bello, 6 1/2 x 9 3/4 x 1 3/4 in (16.5 x 24.8 x 4.4 cm)

SL: Finally, your video Hold Your Earth brings the notion of place, and belonging to a place, to a galactic scale. It is often difficult for us to wrap our heads around what it means to belong to a global community. In both your personal and professional experience, have you come across anything that has helped you keep the big picture in mind while creating works created with such fine detail?

KB: Yes, I have many times experienced these dramatic shifts in scale—how the human scale feels in natural environments, particularly in wide open remote places like coastal environments, where one is facing a large body of water, mountainous environments, or deserts and prairies. For example, when I’m facing a large body of water, such as an inland sea like Lake Michigan, I can appreciate it for its largeness—compared to human size, and smallness—as in the tiny seashells that one finds on the shore, but also for the dramatic scale of time compared to human time when on the same shore one may also find a tiny fossilized coral from hundreds of millions of years ago.

A

Petoskey Stone Katrina Bello found at Lake Michigan, photo courtesy of the artist

When these remote places are having dramatic weather, the sense of scale can feel even more pronounced. This sense of our human scale is perhaps what makes me drawn to working in a way that keeps me outdoors, wanting to be outside to research and observe, find references in the natural world, and be physically engaged with my natural surroundings. I really feel that the nonhuman natural world we live in helps us understand our humanity, reminds us of what’s important—that even the most minuscule things matter as much as the larger things.

Hold Your Earth, 2025. Looping single-channel silent video embedded in media player, 7 1/2 x 11 in (19.1 x 27.9 cm)

Learn more about Bello's relationship to the landscapes that inform her work in Terra Madre, on view through August 30.

Studio photography by Molly Wagoner, courtesy of Zane Bennett Contemporary Art

About the author

Spencer Linford