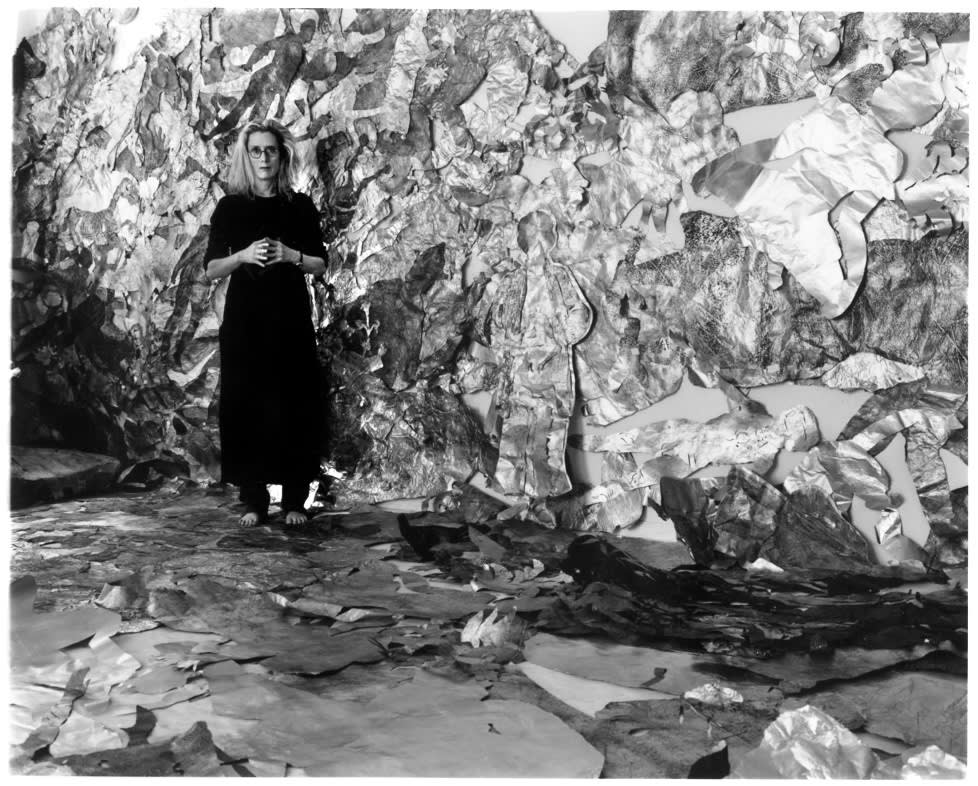

Contemporary artist Lesley Dill elevates and provokes her chosen mediums to dazzling effect, from tea-stained paper to 19th century poetry. Read on for an exclusive interview with the Brookyln-based artist, whose mixed-media artworks grace the Zane Bennett collection.

This interview was conducted over the phone from Dill's studio in Brooklyn, NY.

YOU'VE SAID THAT A BOOK OF EMILY DICKINSON POEMS, GIVEN TO YOU BY YOUR MOTHER, WAS THE CATALYST FOR YOUR VISUAL ART PATH. DID YOUR MOTHER OFTEN SHARE BOOKS AND POETRY WITH YOU GROWING UP?

I must unfortunately answer no. My mother was a theater and drama teacher so she had great influence on me in terms of my turning into an opera director, and of course all of my performance work. Her verve and inspiration and confidence in theater was enormously impactful to me. I have no idea why she gave me that book, but I'll have to ask her! She is still alive at 92.

YOU'VE SAID THAT EMILY'S WORDS WERE LIKE "ELECTRIC BLUE LIGHTS" IN YOUR EYES, OR "ELECTRIC BLUE HUMMINGBIRDS." DID YOU HAVE A SIMILAR ASSOCIATED VISION OF ROSE, FOR EXAMPLE, IN THE WORDS OF FLANNERY O'CONNOR, THAT LED TO THE ROSE FLANNERY DRESS YOU'RE COMPLETING NOW FOR THE FIGGE?

What an interesting question. I think what happened back then was a flash of connection. Perhaps the only way I can describe it is by saying that the light of the atmosphere surrounding the experience was tinged with some beauty of a color, and that color felt like it was blue. You know the beautiful cobalt blue you see in stained glass windows? That is how I would articulate my memory of that experience. It would be lovely if that happened again with different colors and different writers, but I actually wouldn't want it to. It was so electrical that it would be too much.

Even today, when I'm involved with a quite enormous research project, like I am for the Figge show, I'm reading Flannery O'Connor—and I find her to be very difficult—and I get over excited. Just the act of reading any kind of language where I know it's for my intuitive self, my art-making self, it feels so incredibly important that I have to plan very carefully. I think, I'm going to sit here on the couch, I'm going to have just this amount of iced tea, and I'm going to make myself do this for a certain amount of hours, because it always feels a little raw. It's raw in the intimacy of trying to open up a place within me where words can have an effect on my emotions.

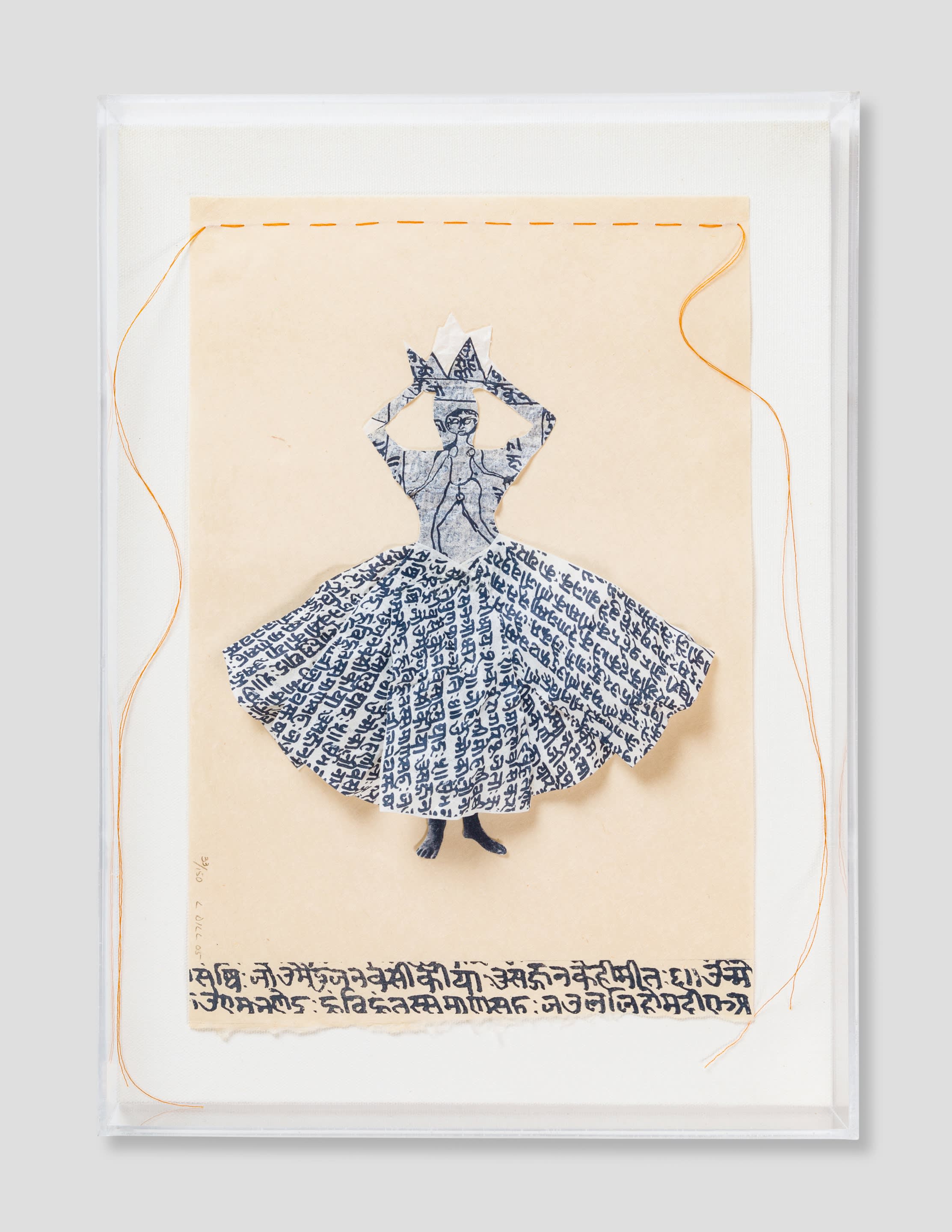

Lesley Dill, Poem Dress of Circulation, multimedia assemblage lithograph.

In many ways you are creating your own poetry in these works, by hiding or obscuring lines and re-forming its structure and rhythm. Would it be fair to say you are engaging in a radical, experimental form of poetry and prose?

I wouldn't call myself a poet. I would call myself a thief and I should go to jail for disrupting these poets' and historical writers' quite wonderful writing. But you can call me a poet! I can't praise myself for something that in a way I see as a flaw—words don't come to me, in terms of connecting myself to the world in a way that's important.

So how I find a way to inspire, is by finding a way to wake up, by arranging, slightly rearranging, by cutting, by braiding. It's then that I am in the swim of my own intentions. And when I'm inside the swim, it's from that place that I work with words.

YOU MENTIONED THAT YOUR HIGHLY COLLABORATIVE STUDIO PROCESS HAS BECOME AN "ART FAMILY" TO YOU. HOW LONG HAS YOUR STUDIO MANAGER SARAH INGBAR BEEN WITH YOU AND HOW DID YOU FIND EACH OTHER?

Sarah is fairly new for me and I found her through Leslie Garrett, director of Nohra Haime Gallery in New York where I'm represented. Both Leslie Garrett and Sarah Ingbar are actually roller derby people! Or roller derby women, I should say, since it's the women's team that's the strongest here in New York. Of course that was not the key thing on her resume that drove me to hire her but she's fabulous to work with, and she lives only five blocks away from me here in Brooklyn Heights.

This is how it works for us now: today, for example, she's going to finish the Emily Dickinson wall scroll. She'll text me, and then I'll go meet her outside her apartment building. She will put the package on the ground and then walk away 10 feet. Then I'll approach and pick it up, and walk away again. And then we'll shout to each other through our muffled masks.

IT SOUNDS LIKE YOU'RE BOTH SPIES ON THE SAME TEAM, EXCHANGING GOODS.

We are! And there's more teamwork going on. I just FedExed Hae Min Yun, my costume designer, Flannery's skirt because I want to add strips of fabric to the bottom and also she'll sew in the thread guides for my stenciling, and we also want to do a fabric head for Mr. Horrace Pippin. So all that gets boxed up.

And then later, when I came home, there was a box from her waiting for me with all 16 name banners of all 16 personas, with all the dates of their births and deaths, and one big scroll. She has 4 more to go. And then Alannah Sears, who lives in Inwood, is working on the Shakers series. So we also use UPS with Alannah to send things back and forth. It's all a slightly nervous experience as you can imagine in the art field. But this is working.

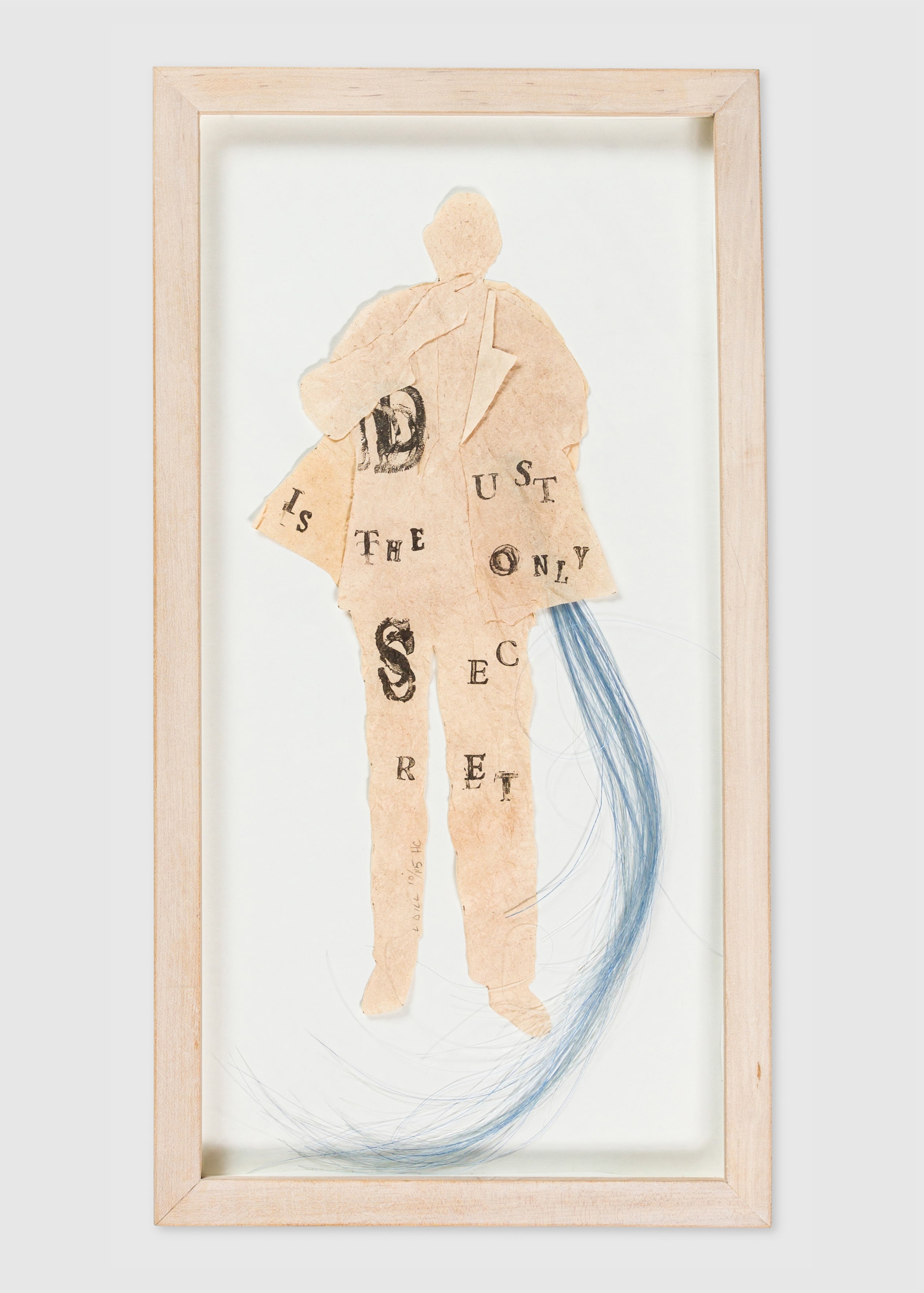

Lesley Dill, Listen, lithograph with blue horse hair on tea-stained paper.

Your fabric works are often thinned and elongated, as if these wearers are larger than life, while your print works seem to play with the paper doll figure, as if the fit is measured for a little girl. What is your intention by creating your own bodily forms for these perceived figures or wearers? Are you envisioning a body when you're creating?

When I make 8 ft tall sculptures or 40-inch paper dresses, I think of the garment as an actual persona. Instead of doing a head, for example, I may just do a portion. My hope is that the mental and cognitive processes of the mind and head are actually embodied in the garment, because of the words. So the words stand in for the function of a body or head. Maybe that's a stretch.

But when I do tiny things, like the small, roughly 10-inch dolls I've been making in the past couple years as an antidote to these big people, then I can do a head-because it's like one breath. It depends structurally. All of these big people are completely flat, so that from the side you just see a line.

That comes from my wanting to be big and powerful and to be little and invisible at the same time, something that, I would like to say, we women often feel-that we're small, but we'd really like to be big. Dickinson wrote to this point: "How ruthless are the gentle." Isn't that fantastic? I love that phrase. Just five words. And she's speaking for us.

HAVE YOU HAD A CHANCE TO CATCH ANY OF THE RECENT DICKINSON BIOPICS SINCE WE'VE BEEN IN SELF-QUARANTINE?

IN LISTEN, 2004, YOU INCORPORATE DYED BLUE HORSE HAIR INTO THE WORK, WHICH IS QUITE FANTASTICAL. WHEN DID HORSE HAIR ENTER YOUR USED MEDIA AND WHY?

Actually, it started when I was doing a print at Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque. I wanted to do some weird image with a Dickinson poem, "Renunciation - is a piercing Virtue -(…) / The putting out of Eyes -." So I cut out two eyes and I wanted horse hair coming out of the eyes. So where do you get horse hair in Albuquerque?

Marjorie Devon, who was the director then, took me and introduced me to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, and Jaune had a horse Blanco, who of course had white hair. She said I could go out to the yard and I could cut some from Blanco's tail. So that started my use of horse hair. To this day, I am still very connected to Jaune.

Because of this upcoming exhibit at the Figge [Museum in Davenport, Iowa], I'm going to be doing a sculpture of a Meskwaki Nation historical figure, and Jaune told me I had to get in touch with them out of respect and honor before I did any work. So she's been my mentor and my guide in connecting me to the many truths of Native American life.

Lesley Dill, Woman with Hindi Healing Dress, lithograph with collage elements.

And finally, how is Brooklyn at this time?